Everyone Hates Their Leader

It doesn't matter what leaders do. It matters that they're in charge.

In January 2025, Donald Trump returned to the White House with a net approval rating of +12, his best showing since 2017. By the following December, it had cratered to -11. That 23-point collapse tracks the most rapid decline for any second-term president in modern polling history.

This would be great if it was just Donald Trump’s problem.

Across presidencies and the world, the best predictor of approval is whether or not that person is, well, governing. Keir Starmer won the British general election in July 2024 with the largest Labour majority in decades. Eighteen months later, just 18 percent of Britons view him favorably while 72 percent hold a negative opinion of him. A majority of people who voted for Labour now disapprove of him. In Germany, Olaf Scholz entered office with 65 percent approval; by the time voters handed him the SPD’s worst result since 1887, that figure had collapsed to 21 percent. His successor from the opposing party, Friedrich Merz, now sits at a 32% approval rating. And there is Joe Biden, who experienced a 28-point approval collapse during just the first year of his presidency, and never returned to net approval for the remainder of his term.

The consistency of this phenomenon across ideology and national context is what makes it so striking. Scholz and Starmer governed from the center-left; Trump governs from the populist right. Germany has a parliamentary system with coalition governments; the United States has a presidential system with unified party control. Britain’s Labour Party inherited 14 years of Conservative mismanagement; Trump inherited an economy that most indicators suggested was functioning reasonably well. None of these variables seem to matter. What matters is holding power. The act of governing itself has become politically toxic in ways that transcend the specific policies being pursued.

For years, the explanation for the global unpopularity of incumbents was explained by COVID fatigue and inflation. Voters just punished whoever happened to be holding the bag. That theory made sense in 2022. It doesn’t in 2026. Nearly every global leader since has turned over (even if they have come back to power since) and yet the precipitous decline in popularity remains.

This is not to say voters are ungrateful or expectations unrealistic — though both may contain truth. Rather, it is an observation that something fundamental has broken. Voters rejecting unpopular leaders is hardly new. What is new is that nothing and no one seems to be popular. The feedback loop between governance and public opinion has collapsed.

The Life and Death of the Political Feedback Loop

A feedback loop is a simple concept: an action is taken, results are observed, and adjustments are made accordingly. In politics, this is how you win elections. Elected leaders propose or implement policies, the public’s reaction is captured, and leaders adjust accordingly. The incentives align: do popular things, deliver results, stay in office.

But voters rarely observe government directly and make their judgments independently. The press serves as the instrument through which the public observes and judges governance. Leaders make changes, the media reports on it and analyzes it, and their coverage shapes how voters understand what has happened.

In the 20th century, the media’s role in the feedback loop reinforced democratic policymaking. The Fourth Estate – composed of just a handful of broadcast news stations and papers of record – were political insiders just as much as the lawmakers themselves. They understood the levers of government and knew the decision makers personally. This familiarity provided the context to cover government in a way that reflected how it actually worked: slow, constrained and conflicted by trade-offs publicly invisible. When Walter Cronkite told Americans that Vietnam was unwinnable, it wasn’t a “hot take.” His pronouncement carried weight because viewers understood he had perspective into the situation they didn’t, and he had earned credibility over decades of balanced reporting.

That model is no longer.

If twentieth century media reinforced democratic accountability, twenty-first century media is eroding it. Twitter accounts, Instagram infographics, Twitch streams, TikTok videos – none are bound by the principles or credentialing that once governed the press. Digital-age commentators can live far away and detached from the events they opine on – sometimes in different countries entirely. They have few relationships to lose when they report facts erroneously. The medium demands that coverage is instantaneous, well before anyone can reasonably judge the impact of events or proposals. The result is a public that is now misinformed about how government and democracy actually works. Their policy and political judgements, informed by digital media, have become untethered from actual outcomes, merits and impact entirely.

One striking example was Keir Starmer’s proposal to institute digital IDs. It was an idea that had long been popular with the British public for its promise to cut back on employment of illegal migrants. Last year, polling found that 53% of the British public supported digital IDs, with right-wing voters more in support than left-wing voters. Prime Minister Starmer announced plans to implement the policy, and polling instantly collapsed. In the Fall, polling found that just 31% of voters supported the proposal.

This is a phenomenon that could only have happened in the 21st century.

In the old information environment, a policy proposed by a new government would have been covered with context: here is what the government is trying to accomplish, here are the trade-offs, here is how similar efforts have worked elsewhere. Voters would have received information that helped them evaluate the policy on its merits. In the new environment, the coverage was instantaneous, shallow, and optimized for outrage. The public’s reaction did not reflect the actual merits of the proposal, whatever it may be. It reflected the reaction to the reaction to the announcement of the policy.

The result is a political system where the connection between governing and popularity has been severed. Leaders can do everything right, everything wrong or do nothing at all, and watch their approval go in a seemingly random direction. The information environment isn’t set up to complement democratic policymaking. The old feedback loop gave leaders room to implement, information to adjust for, time for results to materialize, freedom for the public to observe outcomes accurately and judge them accordingly. The new one renders a verdict before the policy has left the building. And when the feedback loop no longer connects actions to outcomes, democratic policymaking as we know it stops working as it should.

Damned If You Do, Damn…

The implication of this new paradigm is that incumbents face a stark reality: maybe it is impossible to be popular.

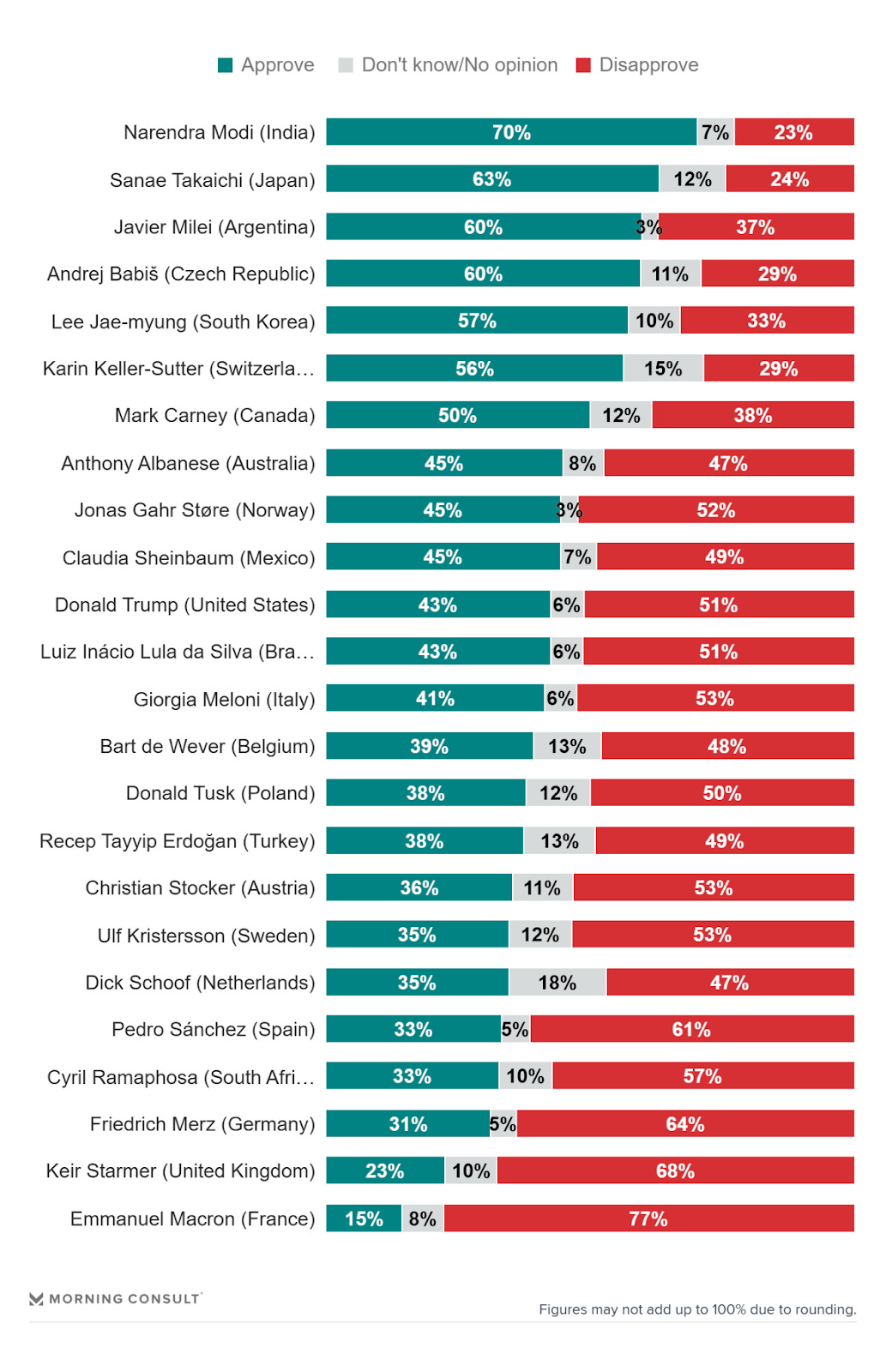

The polling for world leaders looks bleak. A Morning Consult poll finds that only seven major world leaders have net approval ratings, and only two of those seven have been in office for more than a year.

It’s not to say that every one of the world’s unpopular leaders is being judged unfairly. But some of these disapproval numbers are outright absurd. I have not been particularly impressed with Keir Starmer’s job performance – his tenure thus far is eerily reminiscent of Joe Biden’s own failings during his presidency. But according to a poll done by YouGov, Keir Starmer is about as unpopular as Hamas in his own country. While his inability to deliver on major parts of Labour’s manifesto is disappointing – particularly in a country where the governing party has essentially unchecked power to pass legislation – his failings don’t seem up to par with terrorism.

A frequent solution proposed by elected leaders and party strategists is that better “messaging” is needed, and with it they can sway the public to the merits of their accomplishments and overcome the information environment structured to oppose them. Pundits engaged in a near-constant drumbeat of providing Biden with messaging guidance to help reverse his ailing public perception. And now even Trump has landed on “better messaging” to help reverse his falling approval numbers.

It hasn’t worked and it won’t work. The problem is that no message, no outcome, no positive impact or meaningful policy reform can counteract the digital amplification of whatever contradicts it. The digital media environment is structured to amplify content that evokes emotion – and what’s more potent than outrage, anger and condescension?

All of this is reminiscent of one of the more poignant books I have read: The Revolt of the Public, which posits that the digital information explosion has shattered the 20th-century elite monopoly on authority, empowering a fragmented public to tear down existing institutions without constructive alternatives. The book is diagnostic rather than prescriptive. Gurri doesn’t offer a solution because he doesn’t think one exists – at least not one that can be implemented by the institutions currently under siege.

What makes Gurri’s framework so compelling is that it explains why even the politicians who seem to have mastered the new media environment cannot escape its consequences. Donald Trump is the obvious case. In 2016, he used the fragmented media environment to bypass the gatekeepers who would have filtered him out, speaking directly to voters in a way no previous candidate had managed. He understood that the platforms rewarded provocation, and he provided it relentlessly.

But the dynamics that elevated Trump are now helping to destroy him. Despite winning an election on the promise to implement extreme tariffs and crackdown on immigration, many of his same voters now dislike him for doing so. Social media has fueled and driven the renewed Epstein scandal – once a right-wing crusade that has now been co-opted by the left to needle the President at every turn. Trump is being beaten down by the very information ecosystem that aided his two ascents to power.

No Exit

I wish I had a solution to offer or a clear vision for future change. I don’t.

Better candidates and better policies are good, and they are worthy goals that we should pursue. But the structural forces driving permanent unpopularity are not ones that can be fixed alone by that.

The optimistic take is that we are still in the midst of a transitional period as liberal democracies adjust to a new media environment, one that, in theory, we should emerge from. Our current institutions will persist but change, lawmakers will understand new media incentives and voters may grow tired of permanent outrage.

What I worry about is how much worse the pain is going to get before we enter a new equilibrium. The printing press took centuries to produce stable democratic institutions. Radio and television took decades. In between those periods was not great. We are barely fifteen years into the social media era, and the trajectory is not encouraging.

So is incumbency dead? Not quite. But the old bargain – govern reasonably well, earn support – may be. What replaces it is anyone’s guess.