Encampments Aren’t Compassionate

America’s new mayors are reviving a moral and policy failure.

Major American cities have experienced an explosive growth in unsheltered homelessness – the population living on streets rather than in shelters. In Portland, Oregon, just prior to 2008, 1,438 unsheltered homeless individuals were counted; by 2025, that number nearly quadrupled to 5,398. The reasons for this rise, in Portland and elsewhere, were many: people lost their jobs and struggled to come back into the labor market; severe mental health issues went untreated; housing costs continued to outpace wage growth; and the country’s drug crisis accelerated.

Cities can’t keep up. At first, the reason was money: city budgets, devastated by the financial crisis, simply did not have the capacity for many years to meet growing demand for shelter beds.

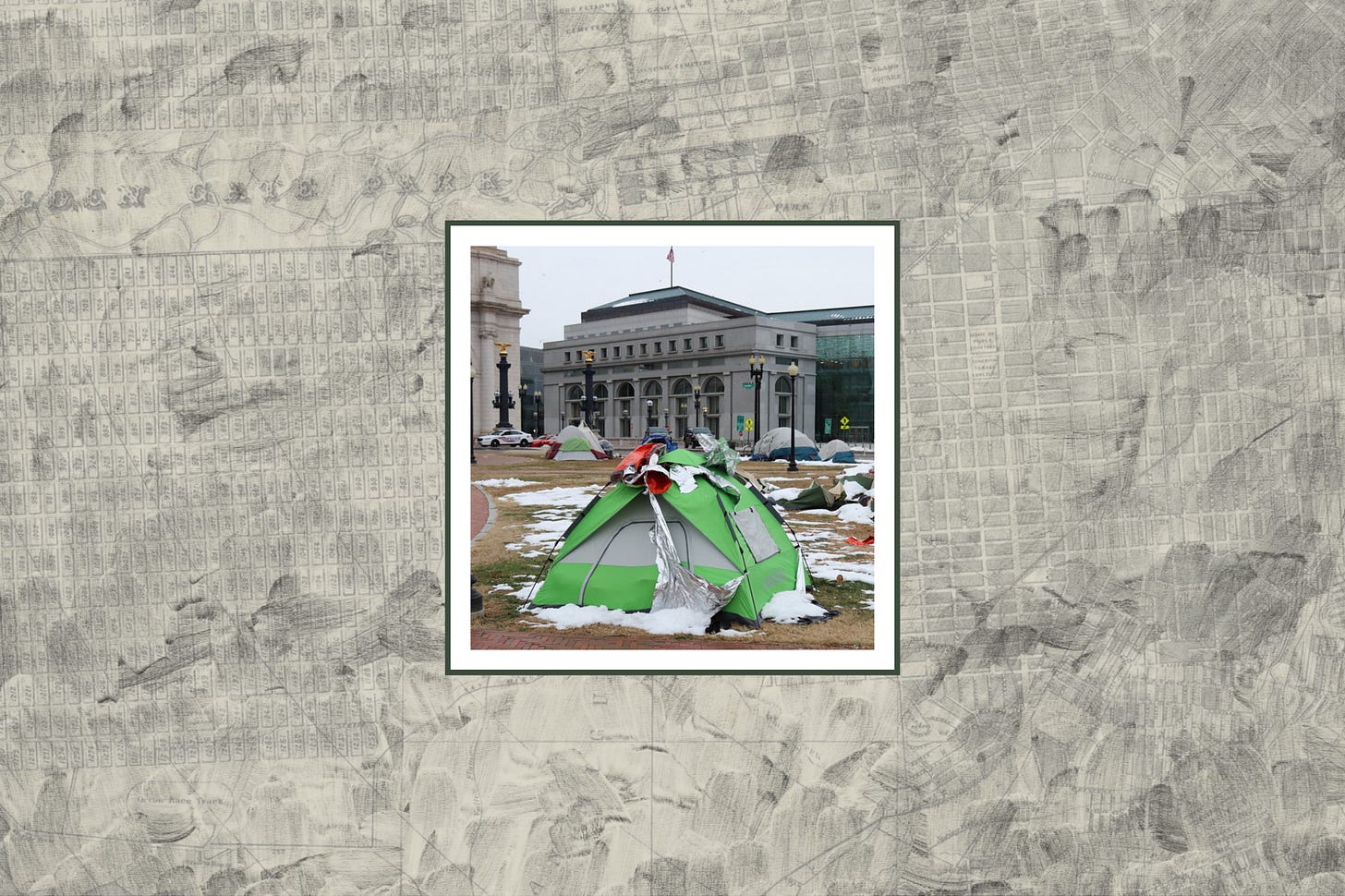

Gradually, the reasons became policy decisions. In DC, the city has long been able to offer shelter beds every night to anybody who needs one, yet historically, it would take months, if not years, to clear homeless encampments. A similar dynamic unfolded in Seattle – despite periods when shelter capacity sat unused, directives and political hesitation limited the city’s ability to move homeless individuals into shelters.

The hesitancy to enforce anti-camping laws was reframed by advocacy groups as a success. The National Health Care for the Homeless Council argued cities should “preserve personal autonomy and decision-making and do not force encampment residents into shelters,” stating, rather bluntly, that “shelters are not housing.” Academic researchers from HUD’s own studies documented that encampments offered “a desire for autonomy and privacy” that shelters couldn’t provide, with residents preferring camps for their “self-governance” and freedom from shelter rules about pets, partners, curfews, and possessions.

Then the political tide shifted. Cities, exhausted by an explosion in antisocial activity brought on by COVID-19, began letting up on their leniency.

Take Denver, where Democratic Mayor Mike Johnston launched a citywide program to clear encampments. It worked: a third-party evaluation by the Urban Institute found the initiative reduced large encampments by 98% and unsheltered homelessness by 45% since 2023. A 2024 Supreme Court ruling, City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, removed a legal precedent preventing stricter enforcement, allowing cities to enforce public camping bans with fewer restrictions.

But fast forward to now, and the policy of permissiveness is making a comeback. Two of America’s newly elected mayors – Katie Wilson of Seattle and Zohran Mamdani of New York – want to again restore leniency toward homeless encampments. It is a well-placed desire to help the most vulnerable in our society. It is also a policy of compassion misplaced – leniency that will damage our cities and the very people it seeks to help.

In Many Cities, Beds Exist — But Go Unused

For a long time, encampments were defended on the grounds that there simply weren’t enough beds. But in city after city, the opposite is now the case: shelters are underutilized while people sleep outside.

Los Angeles: A 2024 audit found that about one in four city-funded shelter beds went unused, costing taxpayers roughly $218 million over five years.

New York City: The Gothamist reported that “more than 1,000 shelter beds and several hundred family units” sat empty in the system.

Colorado Springs: Local officials report that about 200 shelter beds go unused every night, even as the city steps up enforcement on illegal camping.

Minneapolis: County officials told reporters that 30–40 shelter beds, plus more than 40 private rooms for families, go unused every night, despite visible unsheltered homelessness.

Philadelphia: The city operates about 5,000 emergency shelter beds for about 4,300 homeless individuals at any given time.

City officials acknowledge that not only are there empty beds, but they often can’t give them away. In Seattle, less than half of the 1,072 people referred to shelters in 2021 actually went, prompting a deputy human-services director to concede, “We can’t overrule someone’s decision to decline shelter.” In San Francisco, former Mayor London Breed has said outreach workers see about 60% of shelter offers refused, despite the city maintaining “more shelter available than ever.”

Refusals usually come down to specifics — safety, schedules, partners, pets, and what people can bring inside. Those obstacles matter. But the correct response to inadequate shelters is to fix them — not to accept a policy where public spaces become de facto housing while empty beds sit empty a few blocks away.

Cities that treat shelter refusal as the final word have decided, in effect, that the preferences of someone in crisis should govern how public infrastructure is used. But cities enforce rules governing how public spaces are used in countless other contexts, from noise ordinances to health codes. Homelessness should not be the sole condition under which those standards are suspended entirely.

Why This Is Allowed to Happen

Even many supporters of permissiveness concede that unsheltered homelessness is not, at its core, good for the people experiencing it. The case for tolerating it rests on a deeper moral impulse: a fear of pushing around vulnerable people. This manifests as a reluctance to enforce anti-camping laws on people who have nowhere else to sleep, on the theory that enforcement amounts to double punishment.

That instinct has ethical merit. In a liberal democracy that prides itself on human dignity, the idea of chasing someone off a sidewalk for being in a bad place in their life feels, to many, like punching down. Who are we to tell someone to get out when they are struggling just to survive?

The problem, though, is that tolerance comes with its own costs.

A recent review in AJPM Focus finds that health outcomes are worse for people who are living outside.

Mortality for unsheltered homeless people in Boston is nearly three times higher than for their sheltered counterparts.

Research comparing sheltered and unsheltered women documents substantially higher burdens of poor health and victimization among those living outside.

Living in an encampment reduces the odds of becoming stably housed compared to living in an emergency shelter.

Accepting these outcomes in the name of autonomy withdraws responsibility in the name of dignity.

Part of the reason why cities tolerate encampments is that the moral framing offers cover. Elected officials and advocates who oppose encampment clearance can position themselves as defenders of the vulnerable – even when the policy leaves people in conditions that lead to vulnerable outcomes. Opposition to sweeps is easy to articulate and feels righteous. Defending enforcement requires a more complicated argument: that intervention, done right, serves people better than leaving them alone. That’s a harder case to make in a sound bite, even when the data supports it.

Similarly, clearing encampments is combustible – it generates immediate backlash from a concentrated and vocal coalition. Tolerating them spreads the costs across neighborhoods and time. The city avoids a visible “incident” even as it accepts a steady background of disorder and preventable death. The benefits of enforcement are diffuse and statistical; the backlash is immediate and personal. The incentives tilt toward inaction.

The result is a policy equilibrium in which the easiest thing for a city to do in the short term is to do nothing, which is also the hardest position to defend over the long run.

Encampments Are Uniquely Unpopular

Elected officials may avoid taking action on encampments because of the headlines it can draw, but permissiveness is its own kind of political toxicity. A Denver initiative that would have legalized sleeping and camping in public spaces delivered margins that would make Nicolás Maduro blush: 83 percent voted no, just 17 percent yes. Austin passed a similar ordinance with more humble margins: 58-42. When Seattle voters were polled in 2020 about encampments in public parks and playgrounds, 74% of respondents rated the situation as “out of control.” It is nearly impossible to find an issue with so much unanimity as this one.

By homeless advocates, this reaction is often caricatured as reactionary or conservative. But the cities most frustrated by encampments are overwhelmingly left-of-center, places that routinely elect progressive Democrats and support robust redistribution to help the poor. Denver County, where Kamala Harris defeated Donald Trump by 77–21, is not a hotbed of reactionary politics.

It’s easy to see why this sentiment pervades: hundreds of millions of dollars are spent to solve this problem, yet the visuals persist. Voters are willing to fund homeless services, and they have, at scale, but they are not willing to accept permanent public disorder. Sympathy erodes in this situation. That gap between intent and outcome matters.

The political consequences are already visible. Portland didn’t elect Keith Wilson because voters wanted more tolerance for encampments—they elected him on the promise to end street sleeping (he has fallen well short of that goal). San Francisco’s turn toward the center, with the election of Mayor Daniel Lurie and the recall of progressive DA Chesa Boudin, was driven in part by frustration with visible disorder. Muriel Bowser’s approval in Washington dropped from 67% to below 50% over the course of her tenure — the first time in nine years it fell below a majority — with 76% of residents giving her poor marks specifically on homelessness.

The damage extends beyond city limits. Democrats currently face a credibility gap on basic governance – polls consistently show voters trust Republicans more on law and order. That perception is formed by what people see in the cities where Democrats actually hold power. Every story about disorder in America’s cities becomes a data point in a national argument about whether the left can be trusted to run things. Democrats cannot credibly ask voters for power in Washington while visibly failing to maintain public order in the cities they run. Local competence is the price of admission for national ambition.

Getting People Indoors Must Then Be the Priority

The core objective of any city’s homelessness response should be getting people inside. Everything else depends on that foundation. This means shelters have to actually work.

Facilities plagued by theft, violence, and chaos drive away the very people they’re meant to serve. When someone refuses shelter because they’ve had belongings stolen or been assaulted, the refusal is rational. The answer is not to accept that refusal as final, but to fix what’s broken. Some cities are beginning to experiment with alternatives: San Francisco is piloting stabilization units that provide clinically supervised environments for people who cannot function in traditional shelters. Early signs are showing promise. This costs more, but they also could work better: a shelter bed that goes unused because people won’t accept it isn’t actually saving money.

But functional shelters alone are not enough. Cities must also be willing to enforce anti-camping laws when beds are available. This is where progressive cities have most consistently failed: a lack of political will. Laws cannot function as empty threats, and shelter systems cannot operate on a purely voluntary basis when impairment is persistent. We already recognize, in other contexts, that intervention is sometimes necessary because someone cannot make decisions in their own interest. Homelessness should not be the sole exception to that logic, particularly when the alternative is leaving someone to die on a sidewalk.

The enforcement question, though, only addresses the visible crisis. The deeper issue is why so many people end up unsheltered in the first place. As Jerusalem Demsas points out, the cities with the highest poverty rates often have the lowest rates of homelessness. Rates of mental illness and substance use don’t correlate with homelessness either. What does correlate is housing costs and vacancy rates. Someone with a serious mental illness may struggle to hold a white-collar job but manage shift work at minimum wage. That income may be able to afford rent in Tulsa or Memphis. It cannot in San Francisco or Seattle. The progressive cities most vocally committed to helping homeless populations are often the same cities whose housing policies have made homelessness inevitable for anyone who falls behind. Building more housing – not just subsidized units, but market-rate supply that relieves pressure across the entire market – is essential to reducing the inflow of people onto the streets.

What makes this so politically difficult is that every piece of the solution is hard. Enforcing anti-camping laws invites protest and litigation. Reforming shelters means spending more per bed. Building more housing means fighting neighborhood opposition. Pursuing them together requires a sustained commitment that outlasts election cycles. It is far easier, in the short term, to convene a task force, announce a pilot program, and wait for the problem to migrate. That is what most cities have done. It doesn’t work — not politically, and not for the people it purports to serve.

Encampments persist not because cities lack compassion. They persist because elected officials are caught in a political system that incentivizes inaction and reinforces it as compassion. Rejecting that system is not a repudiation of progressive values.

Thank you for writing this. I can imagine coming back to it over the next few years.

One thing this article gets right is that allowing large homeless encampments is not compassionate. It’s neglect dressed up as empathy.

Where many people go wrong is confusing feeling bad with doing good. Refusing to enforce basic laws against camping, drug use, theft, and public disorder hasn’t produced dignity or stability. It’s produced human misery, addiction, crime, and unsafe public spaces. That’s not kindness. That’s abandonment.

Here in Texas it's far from perfect, but we have largely avoided the scale of humanitarian crisis seen in places like Portland, San Francisco, and Seattle precisely because we still believe in enforcing baseline standards of public order while pairing that enforcement with shelters, services, and treatment options. We aren't perfect but we're trying. And compassion without boundaries isn’t compassion... it’s chaos.

A society that will not enforce its laws ends up enforcing suffering instead. The result isn’t freedom for the vulnerable. It’s a slow-motion humanitarian failure played out on sidewalks and under overpasses which gets broadcast on the evening news while attempting to blame elected officials.